Foundation Models in Medical Imaging: A Review and Outlook

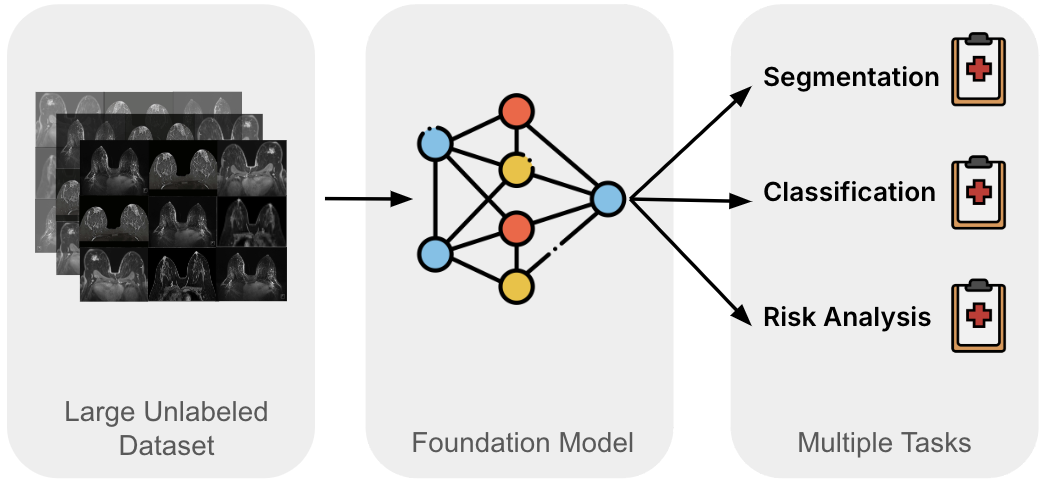

Medical image analysis has traditionally relied on specialized solutions, each optimized for a particular modality, task, or dataset. While effective in controlled settings, these approaches struggle with the realities of clinical practice: limited annotations, significant domain shifts, and wide variability across institutions and imaging technologies. Foundation models offer a promising alternative by learning reusable representations from large-scale data and adapting them to many downstream tasks. This review highlights how this paradigm is shaping medical imaging today.

Technical Background

Foundation models in medical imaging build on a few core ideas. Central to the approach is large-scale pre-training, where models learn general representations from broad and diverse data before being adapted to specific tasks. Insights from scaling laws and emergent behavior suggest that increasing data, model capacity, and training signal can unlock capabilities not present at smaller scales.

Technically, these models rely on flexible architectures—commonly convolutional networks, transformers, or hybrids—that are designed for reuse across tasks. Self-supervised learning is the dominant pre-training strategy, with discriminative, generative, and multimodal objectives. Downstream adaptation ranges from lightweight probing or prompt-based strategies to parameter-efficient or full fine-tuning, depending on task complexity and available data. Together, these components define “foundation” in practice: a scalable, reusable, and adaptable paradigm rather than a single model.

Trends in Imaging Domains

Foundation models are progressing differently across medical imaging domains, shaped by the type of data and clinical workflows.

Pathology has led early development. Models initially focused on individual tissue patches but have scaled to whole-slide images and multi-task applications. Large datasets and high-resolution imaging have enabled strong performance across diverse pathology tasks. Key challenges include representing rare conditions, adapting models originally designed for natural images, and balancing efficiency with contextual understanding. Tile-level models offer practical efficiency and robustness, while slide-level models promise richer context but require significant computational resources.

Radiology has not seen the same rapid development of foundation models as pathology, but steady progress is being made. Recent work highlights the importance of scaling training data, improving data quality, and focusing on vision-specific tasks such as segmentation, localization, and disease detection. Challenges remain, including the limited availability of large-scale 3D datasets, reliance on 2D slices or pretrained networks, and the high computational demands of volumetric model training.

Ophthalmology emphasizes efficiency and multi-modality in 2D imaging. Vision models dominate, as opposed to multimodal vision-language approaches. Fewer models integrate textual reports, and research outside retinal imaging is still emerging. Current work focuses on expanding modality coverage and improving computational efficiency, while ongoing development aims to strengthen clinical integration.

Open Challenges

Despite rapid progress, foundation models in medical imaging face several key challenges:

Data Access and Quality Large-scale clinical datasets are often limited by privacy and institutional restrictions. Public datasets may lack full 3D volumes or diverse imaging conditions. Meanwhile, recent research is also suggesting that careful curation of diverse, high-quality data can be more effective than simply increasing dataset size.

Computational Resources High-resolution whole-slide images and volumetric scans require substantial compute, making efficient architectures and parameter-efficient fine-tuning essential.

Domain Adaptation and Robustness Models developed for natural images need adaptation to medical imaging, accounting for differences in orientation, color, and context. Furthermore, robustness across scanners, protocols, and institutions is critical, as model size alone does not ensure generalization.

Interpretability, Fairness, and Clinical Integration Foundation models must provide transparent outputs, avoid bias against underrepresented populations, and meet regulatory requirements. Continual learning is needed for adaptation to new tasks or evolving clinical knowledge.

Addressing these challenges is essential for translating foundation models from research into reliable clinical tools.