Autotuning PID control using Actor-Critic Deep Reinforcement Learning

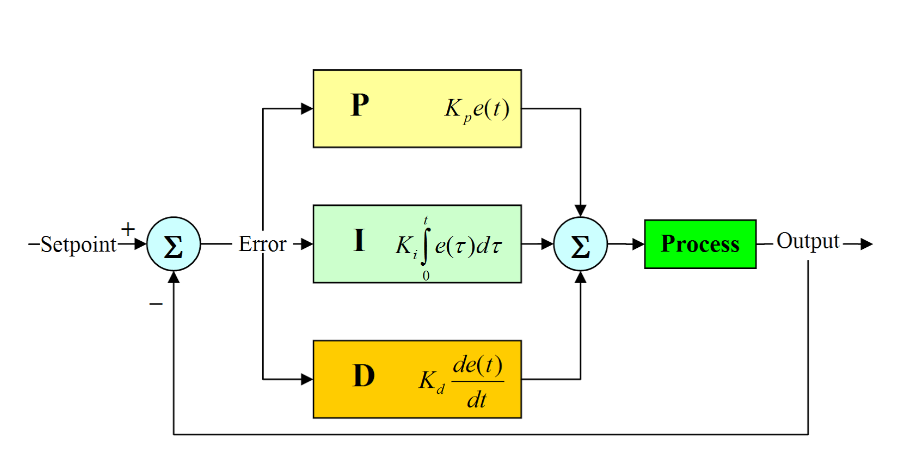

Precise control is essential for robotic manipulation in real-world environments, where actuator dynamics, load changes, and physical constraints prevent ideal tracking of control commands. Classical Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controllers remain the dominant solution for low-level control, but their effectiveness depends heavily on careful tuning of interdependent gain parameters. This tuning process is typically manual, time-consuming, and static: once selected, PID gains remain fixed during operation, limiting adaptability to task variations.

This thesis investigates whether deep reinforcement learning can be used to automatically predict optimal PID gains for a robotic arm performing apple-harvesting motions. The central idea is to replace manual tuning with a learning-based controller that selects PID parameters on a per-task basis, allowing control behavior to adapt to different target positions.

Robotic Setup and Learning Environment

The experiments were conducted in simulation using ROS, Gazebo, and MoveIt, on a two-link robotic arm mounted on a vertical rail and equipped with a gripper. Each joint is driven by a motor with its own PID controller. The focus of learning was placed on the shoulder and elbow joints, as these contribute most to the trajectory error during reaching motions.

Each reinforcement learning episode consists of a complete apple-picking motion: starting from a home position, moving to a specified apple coordinate, and returning to the basket. The state space is defined by the Cartesian coordinates of the apple ([x, y, z]). The action space is continuous and consists of the PID gains ((K_p, K_i, K_d)) for one or two actuators. Gains are constrained to positive ranges to ensure stability.

The reward function is based on trajectory accuracy. During execution, the commanded and actual joint positions are logged, and the total absolute tracking error over the full trajectory is computed and integrated. The negative of this integrated error is used as the reward, meaning that lower tracking error directly corresponds to higher reward.

Learning Method: Advantage Actor–Critic

The control problem is solved using a zero-step Advantage Actor–Critic (A2C) algorithm with a continuous action space. The actor network outputs a Gaussian policy over PID gains, parameterized by a mean and variance for each gain. Actions are sampled from this distribution and scaled to predefined gain ranges using a sigmoid transformation. The critic estimates the state value and is trained using the temporal-difference error, which serves as an unbiased estimator of the advantage function.

Both actor and critic are implemented as neural networks with two hidden layers of 256 units and are trained using the Adam optimizer. Learning rates were carefully tuned to avoid premature convergence and instability, especially when extending from single-actuator to multi-actuator learning.

Experimental Results

Three main experiments were conducted:

Single apple, single actuator

For a fixed apple position, the model was trained to tune the PID controller of one actuator while keeping others at their baseline values. Within approximately 1000 training steps, the learned PID gains consistently outperformed the baseline gains provided by the actuator manufacturer and further refined using classical tuning methods. The learned controllers achieved lower integrated trajectory error and smoother motion.

Single apple, two actuators

The problem was extended to simultaneous tuning of both shoulder and elbow joints. Although this increased the dimensionality of the action space, the A2C agent successfully converged after longer training (≈3000 steps). The resulting PID gains again produced better tracking performance than the baseline controller, demonstrating that the method scales beyond single-actuator tuning.

Multiple apple locations

To evaluate adaptability, the model was trained on 100 different apple coordinates sampled across the robot’s reachable workspace and tested on unseen coordinates. The trained agent generalized well: it predicted different PID gains depending on apple location and achieved comparable performance on the test set. This demonstrates that the learned controller is task-adaptive, rather than merely memorizing gains for a single trajectory.

Conclusion

This work shows that Advantage Actor–Critic reinforcement learning can successfully autotune PID gains for a robotic manipulation task, outperforming carefully hand-tuned baselines in simulation. Importantly, the learned controller adapts its PID parameters based on task context, effectively bridging classical control and modern learning-based methods. These results suggest a promising direction toward adaptive low-level control in robotics, particularly for repetitive yet variable tasks such as agricultural harvesting.